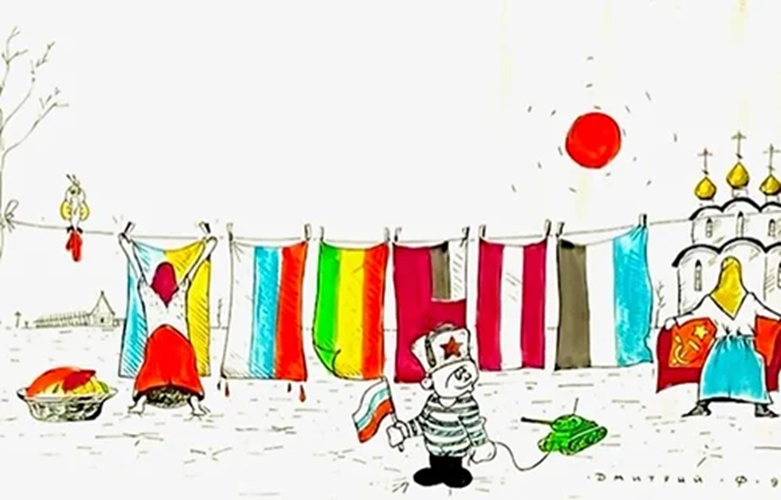

As we reach the unfortunate milestone of the second anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, we continue to see and hear of how the Russian army is working to destroy the human spirit of the Ukrainians. This is done with the strategic goal of “softening” the people to make Russian victory more obtainable. The Russian practice of softening people is not new, the Soviet Union did this with brutal efficiency to its own people for many years. Today let's do a quick review of how one unique form of expression, that of visual art, shared the supported highs and the falling out of favor in the Soviet Union. One thing to always remember about art, sometimes it is to tool that brings a voice to those who feel voiceless. As an example, see the image below and look at the small details.

Description: Image Soviet Protest Art, 1991, Credited to the artist Dimitri. Available on www.contrelemur.com.

Now onto the history!

With the arrival of the political Revolution in 1917, art in Russia would undergo its own revolution. The thoughts of the coming future were filled with possibilities. Lenin believed that before the revolution art had been a privilege only the upper class had access to, and he wanted art to become accessible to the masses. The art movement that would come to dominate the early years of the Soviet Union would become known as constructionism. The goal of constructionism was to make the viewer aware of art, and through it the people and the revolution. This led to the creation of a wide range of art that ran the gauntlet of styles and forms.

Description: Painting Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge, 1919, Credit: El Lissitzky

However, Constructionism would begin losing its appeal with the Soviet elites in 1924 when Lenin died, and the arrival of the Union’s new leader, Joseph Stalin. Under the reign of Stalin, art had but one purpose: the glorification of the Union. Art had become another tool for Stalin. Socialist Realism would come to dominate and would remain a symbol of the Soviet Union.

The socialist realism movement was defined by its realistic style that portrayed only positive images of the Soviet Union and, by extension, Stalin. The images of productive farms, with happy peasants, and tables overflowing with food showed the prosperity of the Soviet Union, while ignoring any issue which might tarnish the facade the government wanted to portray. An example of a topic not expressed would be Holodomor which was man-made famine brought on by Stalin’s collective farming push that would result in the deaths of 3.5 million people in 1932 and 1933. If you check out the painting below by Arkady Plastov titled Collective Farm Celebration, 1937 the image is of plenty and joy with Stalin looking on as a benevolent protector. Probably few in reality where able to share in that type of celebration. Art was used for both propaganda and motivation of the people. If you worked hard for the state, this will be you!

The socialist realism style would continue until Stalin’s death in 1953. The immediate years following Stalin’s death were freeing for the art world of the Union. With the government focused on Destalinization, the destruction of Stalin’s cult of personality, artists within the Soviet Union found themselves free to experiment once more. While there were those who still conformed with the what the state deemed acceptable; nonconforming artists would form small organizations that hosted galleries for their, and other, artists. The works of these non-conforming artist would be considered advent-guard by the west, but to the Soviet authorities these works were deemed “provocative.” However, those artists where able to continue on as the state viewed, they had more pressing issues to address. But nothing lasts forever.

Tolerance for these organizations began to wane in the early 1970’s. Soviet authorities began cracking down once more, but with a gentle bureaucratic touch. Citing that the galleries lacked the proper permits, and the artists would have to take their works elsewhere. Should they refuse, then the police would be involved. However, this “gentle” touch would come to a sudden end in September 1974, when a group of artists organized an outdoor exhibition in Moscow. Dozens of artists planned on exhibiting their work in an open park and began preparations. Gathering their works, they invited friends, family, and reporters. Dozens of paintings would be on display, and, keeping to their nonconformist nature, the artists had erected their works on makeshift easels made from damp wood found from a nearby forest.

Soon after it started, the exhibit ended abruptly when a large force of police arrived with bulldozers and watercannons. The police set about rounding up the artists. An officer by the name of Avdeenko shouted at the artists, “You should all be shot! Only you are not worth the ammunition!” Once the artists were rounded up the police tried to burn the paintings, but the dampness prevented them from burning. So, the police turned to the bulldozers and used their treads to crush the “provocative” art.

This incident would become known as the “Bulldozer Exhibition,” and the aftershock was not what the Soviet authorities had expected. As, among the visitors to the exhibition were Western reporters, who were outraged by what they witnessed, and quickly sent word back to their home countries sharing images and stories. The Bulldozer exhibition was decried by many in the west. Soviet authorities were unprepared for this international backlash, and, to heal their international image, they quickly granted permits to the nonconformists allowing them to exhibit their art publicly. And only a few weeks later the nonconformists would host another exhibition at Izmailovsky Park, Moscow, and it’s estimated that anywhere between 1,000 and 5,000 people came out to view it.

Description: Photograph of police action during the Bulldozer Exhibition 1974, Credit: Unknown

The Bulldozer Exhibition would mark a change in how the Soviet authorities would treat art and its artists. Ground had been given, and soon the laws around art would be loosened allowing for greater freedom of expression. This would result in the rise of Conceptualism, which experimented aesthetically, and was a counter to the social realism of earlier years.

For the remainder of the 70’s and much of the 80’s, most art nonconforming would still be looked down on by the Soviet authorities. There would be the occasional break-up of a gallery, but, for the most part, the authorities were willing to look the other way. This underground art became mainstream in 1988, when Sotheby held its first Moscow auction. Paintings that had once been considered a danger by the state, and were crushed under the treads of bulldozers, were now publicly sold to the highest bidder. Former Soviet era art continues to perform well at international auction houses with the auction house Christie’s having sold the Soviet Union era artist Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935) abstract oil painting Suprematist Composition for $85,821,500 in 2018.

Description: Photograph of Sotheby’s Moscow auction, 1988, Credit: Sotheby

In 1991, the red hammer and sickle was lowered over the Kremlin, and with it the Soviet Union was dissolved. Out of the old, 15 new nations emerged: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

Clifford and the staff at ContreLeMur stand with Ukraine.

_edited.png)

Comments